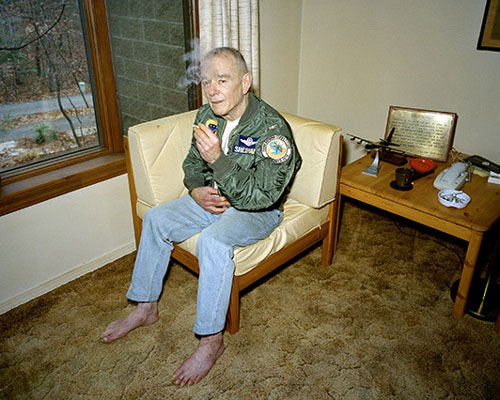

“I was a pilot for Operation Ranch Hand, the 12th Air Commando Squadron, stationed at Bien Hoa. We did the defoliation work spraying Agent Orange with C-123’s. The C-123 was a great airplane for the job because the fuel tanks were right behind the engines and you could salvo them. You could eliminate a burning tank in a second and there were very few fuel lines. This wouldn’t always save you, but it surely helped.

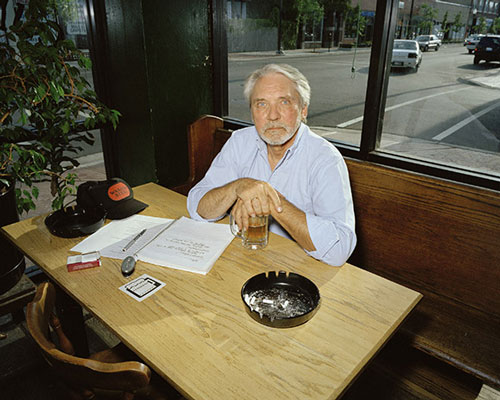

We would typically fly two sorties per day. We would get up in the wee hours of the morning, have a quick breakfast, and go to our preflight briefing. We would then take off in formation and hit the first target exactly at daylight. The theory was that the enemy would still be sleeping and we would get through the first target without any shooting. It was a great theory; however, it just didn’t seem to work. We would fly to the target area at 5,000 feet, and contact a Forward Air Controller who would ‘Smoke’ the start of the target run. Then we would make a really steep descent and start the target run. We were supposed to spray at 100 feet off the tree tops in order to get maximum coverage; but, when the shooting started you had a tendency to really get down on the deck because the lower you were, the safer you were. We expended our 1,000 gallons of defoliant during a four-minute run, and then try to get to a safe area to climb out. That was the longest, most exciting four minutes in the world. Then we would return to Base and do it all over again; we would usually be done for the day before noon.

They were always saying that we were the most shot at, and hit, operation in the history of air war. I don’t know how true that was, but it seemed pretty accurate to me. Nobody ever got through an assignment without their plane taking hits, and at least half the guys had Purple Hearts and not from scratches. We couldn’t bail out because we were too low while the shooting was going on and the plane had spray booms across the back that you would hit if you did jump. As a result we didn’t even carry parachutes. You just had to fly whatever was left of the plane as long as it would fly. My plane got hit on 35 missions and a few of them were pretty bad.

Most of the fire was from small arms; we wore body armor and our seats were armored to protect us. When the enemy would open up with the .50 caliber and other big stuff, it would get real serious. The heavy caliber bullets would go right through anything. They would even shoot rocket-propelled grenades, and one guy came back with a Montagnard arrow out of a crossbow stuck in his airplane. We might be the last military outfit that took hits from a crossbow. You took a lot of hits—that’s all there was to it. I took my first hit on my first mission, and got my last hit on my last mission.

When the shooting started you would really get low because they would have less time to fire at you. I’m sure I was frequently only 25 feet off the treetops. Some of the airplanes had marks where guys hit the top of trees. I was always surprised that no one ever crashed because of getting too low. We were low enough that you could get a real good look at the enemy and see if they were shooting at you or someone else—you would even see kids and women shooting. All of them seemed to be pretty bad shots. We would drop smoke grenades when we took fire and then the fighter escorts would hose down the area with some really bad stuff. It would sometimes look like the Fourth of July with everything going off. You could sometimes see the concussion when the ordnance would go off. If the women and kids were shooting they usually got it too. That bothered me at first. Should you shoot at kids? No. If the kids are shooting at you, should you shoot at them? Yeah, I think so.

The day my Flight Commander got shot down you could see the gun emplacement that fired at him—it looked like a doughnut. They dug a round hole with a quad-mounted .50 caliber in the middle so they could shoot in any direction while standing in the hole. I was on Emmett’s wing when they got him. They hosed him down really good and then turned on me, but the gun must have jammed because they started fiddling with it. Emmett’s plane was burning like crazy—his right wing tank was on fire. I was screaming at him over the radio, ‘Do This and Do That’ and finally his tank dropped off. We were making an escape over the South China Sea and that tank dropped like a huge ball of fire. Then his airplane slowly rolled over and went straight down into the sea.

There were always a few of us whom they kept qualified to carry cargo—we called it trash hauling. When the regular trash haulers got overloaded, we would remove the spray tanks from a few aircraft and install rollers on the floor so you could move pallets in and out easily. I didn’t like the job because it was usually a bad mission. One time I was tasked to haul the explosive charges that they load behind the projectiles in the big guns. The Base was under siege so our procedure was to land, roll to the end of the runway, immediately turn around and take off. The crew slid the cargo out on the take off run. I also hauled some supplies to Khe Sahn during their siege. The place looked like the surface of the moon—the troops lived underground. We just made a touch and go there and the crew pushed the cargo out during the touch. I don’t think any aircraft would have lasted very long on that runway.

I was never wounded, but I surely got scared occasionally. I know a couple of guys that said they were never scared and acted pretty casual about things, but its awfully hard for me to believe that there was no fear in anyone. I would get extremely scared. I felt really bad about the fact that I might not get back to see my kids and not watch them grow up and not get back to my wife and parents.

I don’t know of anybody that was having a great time over there. We would all have rather been somewhere else. I didn’t want to go to Vietnam, didn’t like it when I got there and was happy to leave. But I was a career officer and it was our job and our duty, so I went and I made the best of it.”