Between 1981-85, I wandered around the back roads of southern Indiana, sometimes alone, sometimes with my good friend and collaborator, author Scott Sanders. Bloomington was my new home—I’d come to teach photography at Indiana University. One doesn’t have to travel far before running into the ubiquitous presence of the limestone industry.

Stone quarrying is an extractive industry. Rolling hills are cut and sliced and chunks of it are shipped all over the country. The resulting landscape is a chaotic jumble of gaping holes and rusting steel. Quarries fill with water and become swimming holes—one quarry in Bloomington was considered among our best swimming spots until it was found to be contaminated with deadly PCB’s, dumped from the local Westinghouse plant. People drive cars into abandoned quarries and use the auto bodies for target practice. As Scott points out, the quarries are places of violent activity. I suppose I see them as a kind of elemental battleground where man wages war upon nature.

There is, however, another side to be looked at. For nearly every hole in our backyard here in the stone belt, the serpentine outcrop of building-grade limestone that stretches roughly 20 miles from Bloomington south to Bedford, there is a building or monument somewhere. It is intriguing to identify some mammoth hole in the ground as mother to the Empire State Building. I have followed blocks of Indiana ripped from the ground at Independent Limestone Co. trucked to Bybee Stone for milling and on to the National Cathedral in Washington for carving and installation.

Nature ultimately triumphs; given enough time the land begins to revert to a more natural state and man’s presence begins to disappear. The quarries become new habitats for plants and animals. I’ve seen red foxes hunting among stone piles in broad daylight.

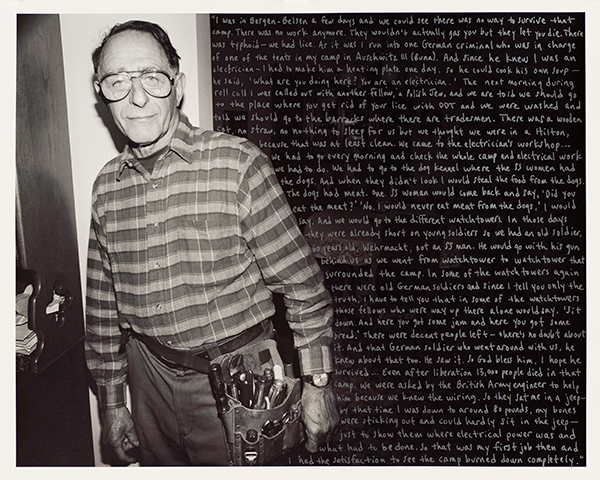

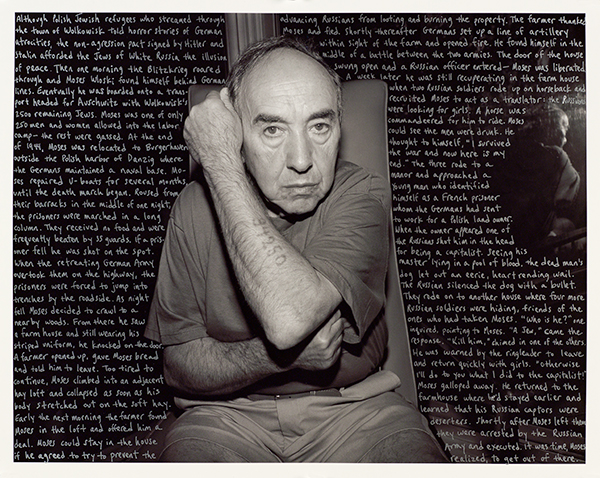

Another aspect of the photographs included in the book concerns portraits of men who work with limestone in quarries and mills. These are blue-collar workers whose fathers and fathers’ fathers made their livings battling massive blocks of stone. I wanted to see through the eyes of my new neighbors to gain insight into their ideas about nature, labor and life.

Most of the photographs in the book were made with an 8×10” view camera—something of a fossil of a camera in our electronic age and somehow appropriate for photographing an antique industry that deals in fossils. The photographs in this book are not to be seen as objective documents. Rather they are intended as personal responses, aspiring toward the poetic, to some thoughts and feelings, some experiences I’ve had in my travels in stone country.

Update

When Gary Dunham, Director of Indiana University Press, suggested that Scott and I consider an entirely fresh, new revised edition of Stone Country, I jumped at the chance. Collaborating with Scott was one of highlights of my career. It was tremendous fun to travel around and share our experiences and insights; and the prospect of working together and building something new was too good to pass up. Our respective careers had taken us far away from limestone in the 30 years since the publication of the original book and I was genuinely curious about what we would find now.

We began by driving to B.G. Hoadley Stone Co. to meet with Pat Fell Barker and her son, Dave Fell, who run the company. They were strong supporters of the original project and we sought their advice as we started up again. How had the industry changed in 30 years? What should we see? Who should we talk to? And were any of the stone workers who appeared in the original book still working for Hoadley? As it happened, the man in the cover photograph, “Blockmarker,” one of my favorite photographs depicting the struggle between man and nature and the massive scale of the stone industry, was still employed at Hoadley. However, the next day was to be his last—he was about to retire.

The following day found us face to face with Larry Anderson, performing more or less the same tasks as he had three decades earlier—grading and marking chunks of limestone freshly ripped from the earth. I re-photographed him standing on a block of stone in a field of stone blocks.

And so Scott and I were off again working on Stone Country: Then & Now, keeping the best writing and photographs from the original edition but adding new materials to bring the industry up to date and, I suppose, to show how we had changed as artists as well. Quarries and mills today are safer and quieter and more automated than they were 30 years ago. Workers are younger. Computers cut stone around the clock.

For the “Works” chapter the Empire State Building and Flatiron and Union Station and other iconic American buildings are joined by the new Yankee Stadium; the Apple Store on Chicago’s Magnificent Mile; and the Pentagon, a section of which was damaged by the attack on 9/11. Independent Limestone Co. provided the stone and Bybee the expert milling, so that the contractors could match up the repairs with the original stone as seamlessly as possible.

I now use a medium format digital camera for my work. And Photoshop allows me to stitch panoramas and overlay images in ways that weren’t really possible in the film era.

And it occurs to me that much of my work as a photographer addresses the element of time. The idea of “then and now,” of observing change incrementally, as only photography’s attention to minute detail allows, has been a central focus in my long term projects. It’s a way of linking past and present, of addressing memory. The limestone series was my first sustained project after moving to Indiana, so there is something fitting about revisiting it as I retire and measure how much I’ve changed in the last 35 years.